By Mina da Rui, LLM student

In 21st century Great Britain, legal reasoning paths are slowly widening as human rights, environmental dysfunction, and animal injustice come to the fore of public consciousness. Animal law is a niche area of law, a tentative but growing jurisprudence. This growth paved the way for an animal law success story recently, one that captured the imagination of our nation’s people, governments, parliaments, media, and celebrities, after almost 10 years of hard campaigning.

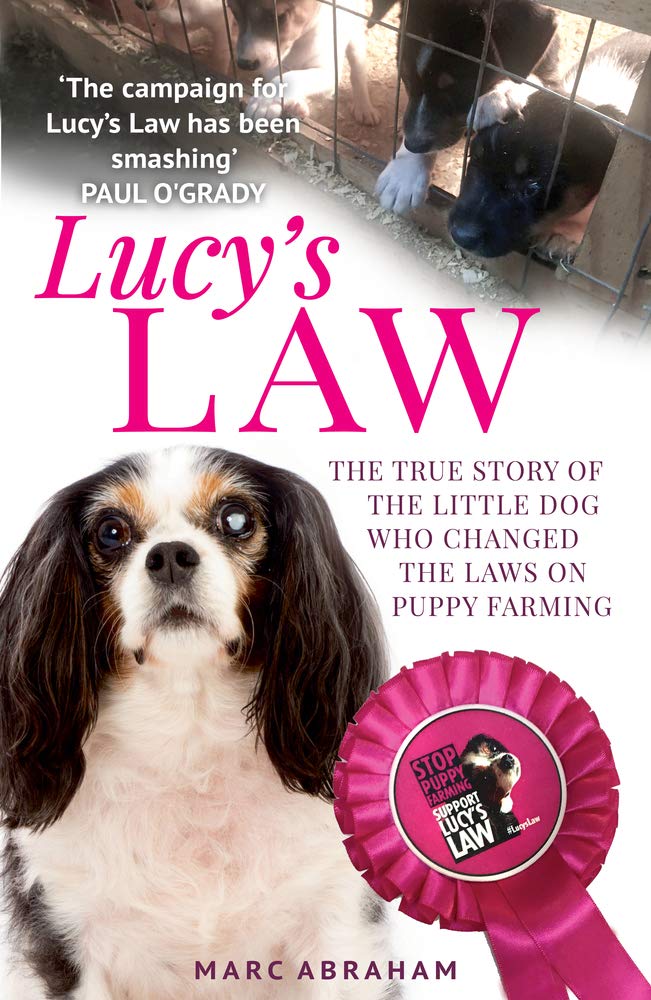

Author Marc Abraham is, along with ex-breeding-dog-turned-canine-celebrity Lucy, the key figure in the campaign. His tale of how the for-profit sale of puppies and kittens by third parties – the basis for the existence of puppy farming, which relies on third-party dealers – came to be banned in Britain, under Lucy’s Law, is every bit the heartening, humbling, and unlikely David & Goliath myth, and contemporary animal justice campaigners the world over can expect to find themselves irresistibly inspired, educated, and encouraged.

The book begins by retracing the paths that led Abraham, little Lucy, and her adopter to this momentous step in animal protection law. The opening pages describe the nightmare Lucy endured on a Welsh puppy farm, the lawful status of which (at the time) is difficult to comprehend in light of its sheer horror. This information alone makes this book essential reading for anyone seeking to understand the commodification dynamics that restrict animal welfare in contemporary society, and the plight of industrially bred animals in particular. The narrative then lifts, intertwining Lucy’s strength in overcoming trauma and pain with tales of the joyful life her caring rescuers and adopter gave her. Given Abraham’s lifelong love for animals of all kinds, these circumstances led him to realise the puppy (and kitten) farming problem and to throw extraordinary energy into conceiving and running the campaign that ended it.

As the paths of Lucy, Abraham, and their allies meet, the reader comprehends the formidable drive for justice that led a handful of caring citizens to this victory, as events, setbacks, ideas, alliances, and parliamentary milestones unfolded. Thanks to its lively, well-paced, and evocative writing, Lucy’s Law is all at once informative, galvanising, and moving. Crucially for any (budding) animal justice campaigner, it is peppered with campaigning and strategy insights from Abraham, who credits his father’s marketing talent, chess lessons, and kindness, along with his grandmother’s astounding resourcefulness and courage, for inspiring some of the campaign’s winning ideas.

Abraham’s book is a thoughtful and detailed tribute to Lucy and to all those who worked tirelessly to campaign for Lucy’s Law to become an actual piece of legislation. It renders a vivid picture of the perhaps surprising obstacles which campaigners for Lucy’s Law were faced with and Abraham provides an eye-opening account of his and his team’s journey, one he clearly hopes will spark desire and careful planning ideas in other campaigners for animal justice.

This intense, instructive, and uplifting read would likely interest those wishing to engage with policymakers and lawmakers to protect animals or to defend other social justice causes. Budding veterinarians may also be inspired by Abraham’s journey to proficiency in animal care and his influential public presence as a nationally recognised spokesperson for animal welfare. Truly, the personable and passionate tone of these pages is likely touch the heart of any animal lover, from their teens upwards. The book has all the hallmarks of the sort of inspiration that sparks the desire in a young person to devote themselves to stand up for justice. As for those of us already settled into adulthood, the book is a testament to the historic progress that individuals and small groups of people can achieve on behalf of animals.

Additionally, this book may shed some light on the difficult problem of anthropocentrism in animal justice. It acknowledges the dogs as commodities through the condoning of the more ‘humane’ forms of dog breeding. It would of course be cynical to criticise Abraham for going with the flow of a culture in which, even exempt from the nightmarish torments of puppy farms, animals are half-objectified, half-anthropomorphised, always commodified and subordinate to human interests. His highly readable account of how ‘a little dog changed the world’ belies a hard but unavoidable notion: In the struggle for animal justice, in order to fight animal suffering and exploitation, campaigners still have to use the language that underpins their commodification in order to be heard. Indeed, the brilliance of the campaign for Lucy’s Law stems partly from Abraham and his allies’ willingness to engage with the often obscure language of lawmakers and politicians. An ode to the power of resourcefulness, relationships, constant strategic reflection, persistence, and teamwork, this book offers a valuable reminder that success and failure both exist in any kind of growth process, and that embracing that process can lead to profound improvements to animal justice.