By Sabina Bravo R., Law Graduate of University of Chile

On October 18, 2019, coordinated demonstrations and mass riots began in Santiago, Chile. A significant portion of society was acting in response to allegations of rising corruption, inequality, government mismanagement, and general injustice. On that first day of what would become a years-long campaign, the demonstrations grew, vandalism proliferated, even the Santiago Metro Network was disabled. The president of Chile declared a state of emergency, but in the following days and weeks the protests escalated and spread throughout the country, in what was considered “the worst civil unrest” since Pinochet’s dictatorship. Within a month, the government responded with the announcement that it would hold a referendum on whether the country would rewrite its constitution. Amid all the momentous changes, this opportunity has given animal advocates a chance at progress.

At that moment, for all those who fought and continue to fight for improvement, a window of light was opened when all doors seemed closed. Following popular elections, it was decided that the body that would draft this new constitution would be made up of people democratically elected for the task. Certain criteria would be considered to ensure a quota of indigenous ethnic representatives was met, along with equal distribution between men and women, meaning this would be the first constitution in the world drafted with gender parity. Many historically segregated and neglected communities were able to have representation in the Constitutional Convention, and the long-sought list of basic social rights would finally be addressed.

With this opportunity for progress, Fundación Derecho y Defensa Animal (Animal Law and Defence Foundation) initiated a campaign called Animales en la Constitución (Animals in the Constitution) and, with it, developed a guide developed a guide towards the goal of including animals in this new Constitution. According to their three-part programme, nonhuman animals must first be recognised as valuable individuals in their own right and not as means to certain ends or as “parts” of a superior environment. Secondly, nonhuman animals must be recognised as having the capacity to feel – sentience (which the UK government is currently determining). Finally, the state must ensure compliance with this standard and promote it throughout the country in an institutional manner. This proposal was presented to more than 300 candidates for the Constitutional Convention, where the election of those who adhered to and committed themselves to the Campaign was encouraged, resulting in the election of more than 60 of them.

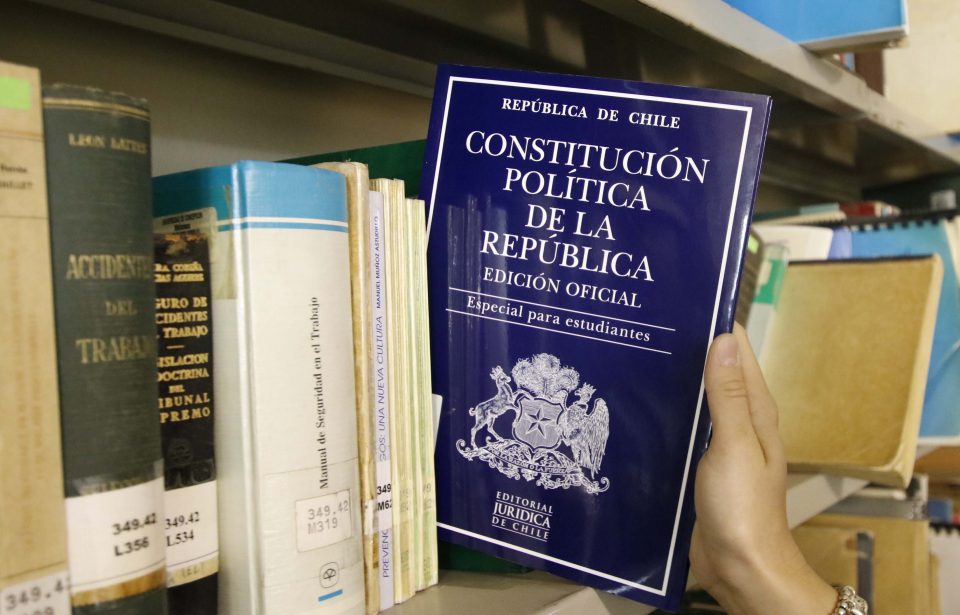

Up to now, legal protection of nonhuman animals in Chile came from three bodies of law: 1) Animal Protection Law (20.380),1 which mentions standards of treatment and care of nonhuman animals in general; 2) legal modification (resulting from 20.380) of the Chilean Penal Code introducing the crime of animal abuse through article 291 bis2; and 3) Responsible Pet and Companion Animal Ownership Law (21.020),3 applicable for a categorised group of nonhuman animals. These laws are insufficient for a true and effective protection of nonhuman animals, and the Political Constitution of Chile, the highest legal norm in the country, leaves nonhuman animals out of the fundamental rights.

The current Constitution of Chile was created in 1980 by a small political group of a single ideology and ratified in a plebiscite amid a dictatorship, one that dragged Chile through systematic violations of human rights.4 For 41 years, this constitution served as a wall to prevent or hinder any attempt to advance towards a different, more equitable and democratic Chile, because of the high quorums it sets for voting on proposed legislation in Congress, among other reasons, that block legal modifications or the creation of new laws.5

Furthermore, article 19 N° 86 of the country’s highest law recognises the right to live in a pollution-free environment, assigning the State the duty to ensure that this right is not violated by protecting the preservation of nature. But it leaves out animals as individuals, making it impossible to extend protection to nonhuman animals in a way that covers all species regardless of the role they play or the space they use within the ecosystem. In practice, this limitation results in the insufficiency of these legal tools, due to the inability to weigh the rights of animals with the fundamental rights of humans. It thus became imperative within the animal movement in Chile to promote the need for protection and recognition of nonhuman animals as individuals with inherent value.

As of today, the campaign continues to gain adherents from all political sectors and is increasingly becoming a reality. Currently, an online voting system is open to support Popular Norm Initiatives, which are created and disseminated by civil organisations or individuals as proposals for norms to be discussed and eventually included in the new Constitution. Among the many initiatives that have been presented is that of Sujetos, no Objetos (Subjects, not Objects), which seeks to give nonhuman animals the legal status of subjects of law and not movable property. Each person can support seven rule proposals and each proposal must have a minimum of 15,000 signatures to move on to the next stage of discussion. This initiative surpassed 19,000 signatures and moved on to the next phase.

In addition, Fundación Derecho y Defensa Animal (Animal Law and Defence Foundation) has participated in various committee hearings, including for the Environment Committee, in order to start the conversation on the inclusion of nonhuman animals in the new Constitution. It has also provided model regulations on the issue to the Convention, making them public through press points to the community.

We believe that including nonhuman animals in Chile’s new Constitution is not the ultimate goal of the animal rights movement, but it will open up many opportunities for education and discussion. It would make our country’s highest law a permeable ally in the journey of a civil society that evolves in values, beliefs, and needs as time goes by. The animal rights movement continues to work with conviction and optimism so that the initiative, which has taken so much effort to establish in our society, can be included in the new Constitution.

*The author is an associate of Animal Law and Defence Foundation. However, this piece is written solely from her individual perspective and not on behalf of the foundation.

Ed. note: This piece was written in early February 2022 and thus does not reflect relevant events occurring after this time.

Other sources:

1: Chile. Ministerio de Salud, Subsecretaría de Salud Pública. 2009. Ley 20.380 sobre Protección de los animales. Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional. / Chile. Department of Health. 2009. Animal Protection Law (20.380). Library of the National Congress.

2: Chile. Ministerio de Justicia. 1874. Código Penal. Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional. / Chile. Department of Justice. 1874. Penal Code. Library of the National Congress.

3: Chile. Ministerio de Salud. 2017. Ley 21.020 sobre Tenencia Responsable de Mascotas y Animales de Compañía. Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional. / Chile. Department of Health. 2017. Responsible Pet and Companion Animal Ownership Law (21.020). Library of the National Congress.

4: Chile. Comisión Nacional sobre Prisión Política y Tortura. 2005. Informe de la Comisión Nacional sobre Prisión Política y Tortura (Valech I) / Chile. The National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture. 2005. The National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture Report. (Valech I)

5: C. Fuentes. Bloqueo desplegado durante las últimas tres décadas: Los candados a la democracia de la Constitución de 1980. Prensa UChile. 2019. / The blockade deployed over the last three decades: The 1980 Constitution’s locks on democracy. UChile Press. 2019.

6: 8 Chile. Constitución Política de Chile. Art. 19 n°8 / Political Constitution of Chile. Art. 19 n°8

![R (on the application of Highbury Poultry Farm Produce Ltd) (appellant) v Crown Prosecution Service (respondent) UKSC [2020] 39](https://news.alaw.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/News-Blog-Image-25-440x264.png)